Imagine your a photon

This was the first portion of my dissertation where I am trying to introduce radiation transport for a more general audience.

Before jumping into equations and math and schemes and algorithms—imagine the warmth of the sun on your face. Feel the golden rays that have danced across the faces of every person you have ever loved, hated, lost, cursed, and indeed every person who has ever lived. You may ask how did resplendent power of the gods come to interact with your lovely face? Before we answer that question we must make some simplifications from the physical truth, tell ourselves convenient lies so we can comprehend an approximation of the truth. There are infinitesimally small packets of energy called photons which for our purposes behave much like a billiard ball would. These invisible billiard balls travel at a constant speed yet can still have differing energies from one another, which we call color. They move on straight line paths between events like bouncing off a material or being absorbed by your face.

Now consider a single photon as it leaves the stellar atmosphere. It and its comrades are traveling in all directions outward, but our photon and a few of its friends are aimed at a pale blue dot in the distance. They travel on a straight line path, streaming through the void region of space, not interacting with much of anything for about 5 minuets—all the while the pale blue dot is growing in size. Once most of the horizon is filled with a view of Earth, some of our photons begin to interact with the air in the atmosphere we breath. Not very often at first in the high altitudes where the atmosphere is thin, but then growing ever more common as our photons get closer and closer to the ground. These ``interactions” are actually some of our photon’s friends smashing into the gas molecules making up the atmosphere itself. Most of that gas is nitrogen which really likes to interact with blue light. These photons are then scattered like billiard balls off of one-another where only their direction is changed. This is why an Eastern Oregon sky (and occasionally a Willamette Valley sky) appears so blue! That’s blue light from the sun hitting the atmosphere tens of hundreds of miles away bouncing off an N$_2$ molecule and heading straight for you!

Our photon, however, interacts with nothing and keeps on that straight line path from the stellar atmosphere to your face. As you turn towards the sun our single photon (and about a gigllion (in the 1e21 range) of its closest friends per second) hits your face. Some of these photons are reflected off in such a way that they will project a rendering of it into little receptors in the eyes of those who get to behold you. Others are absorbed, each one imparting a tiny bit of energy into your skin you feel as heat.

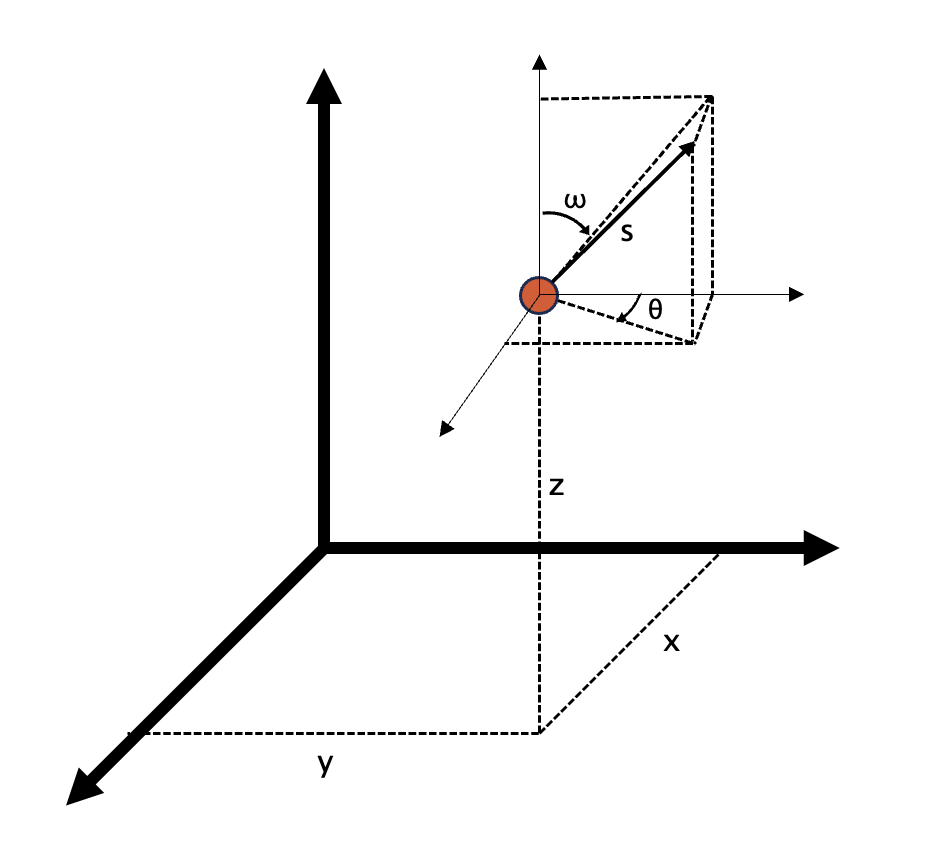

Just as we described this process with words, we can describe it with math using operations which represent streaming, absorbing, and scattering—or more generally sources and sinks of particles of light. We do this because a rigorous mathematical definition has the added benefit of being more generally applicable to other problems. Photons move in three-dimensional space in a specific direction of travel (imagine the photon being at a specific location and and that is pointing in the direction it’s traveling) We need to describe both where the particle is and where that pointer is pointing, meaning to describe a single particle of light we need at least six independent variables. If you allow things to change with respect to time then there’s an additional 7\ths independent variable. This is often referred to as the curse of dimensionality and is one of the things that makes solving these equations so difficult. Not just photons behave like this, streaming, absorbing, and scattering their through the universe—the movement of any neutral particle that doesn’t interact with electric or magnetic fields can be described with similar equations.

For example another problem we are interested in simulating is how neutral particles are moving in problems undergoing nuclear fission. Neutrons (unlike charged particles, and most of the time, photons) can interact with the nucleus of an atom because they are unaffected by the negatively charged orbital electrons and the positively charged core. Some isotopes (Specific arrangements of the subatomic core of a given atom.) readily absorb neutrons into the nucleus, which may make such atoms unstable.

When an unstable atom fissions (breaks apart) , it releases energy along with daughter and subatomic particles, which may be more neutrons, depending on the parent atom. If additional neutrons are released and encounter more material which can undergo this type of reaction, the release of subsequent neutrons can induce a chain reaction. A nuclear reactor’s job is to keep this chain reaction in balance, producing enough heat to boil water, spin turbines, and generate electricity—but not too much heat that the system can’t safely operate. To ensure this process produces enough heat-generating reactions safely, we need to understand where, how, and when neutrons are moving within the core of a reactor. We use more or less the same equation (with some extra terms) to describe how neutrons are born, die, move, and interact within a nuclear reactor as we would photons hitting your face from the sun.

Other times we would want to solve these equations include during cancer radio therapy when we often target neutral particles (like photons at x-ray energies) directly at cancerous cells while trying to avoid healthy tissue as much as possible. Or when we want to model the wall of a rocket nozzle to ensure that it will not melt due to heat transfer from the burning gases. From the more pedestrian engineering applications all the way to accretion disks of black holes, core-collapse supernovae, cores of super-massive planets, and the core of our own sun (where our photon from earlier was born) can, in part, be modeled with equations that look similar to the ones I research.